Johnnie L. Cochran, Jr. was born on October 2, 1937 in Shreveport, Louisiana. His great-grandparents were slaves, and his grandfather was a sharecropper. His father, Johnnie Cochran, Sr., and mother, Hattie B. Cochran, instilled in Johnnie a work ethic that would take him from the Jim Crow Era South to the upper echelon of the American Legal System. Young Johnnie grew up with two sisters, Pearl and Martha Jean, and the siblings grew up in a time when Louisiana was still dealing with effects of The Great Depression and with Jim Crow laws still deeply entrenched. Despite the times, Johnnies time in Shreveport was a happy time and the memories that always stayed with him were made on Sundays with his family and his church.

In the fall of 1943 Johnnie’s father set out to California and quickly found work as a pipe fitter with Bethlehem Steel in the Alameda Naval Shipyards. Just as the young Johnnie Cochran was turning six he and his family boarded the Southern Pacific and headed to California as part of the second wave of the Great Migration, where 6 million African Americans moved to the Northeast, Midwest and West. Initially they lived with Aunt Lucinda, but soon found their own place near the shipyard. It was the family’s first experience with an integrated neighborhood where working class people of all races and religions lived side by side.

In 1949, a year after accepting his promotion and moving to San Diego, Johnnie Cochran, Sr. was offered another promotion and was asked to move to Los Angeles, where Golden State Mutual was headquartered. The family packed their belongings once again and moved to the city that Johnnie L. Cochran, Jr. would call home for the rest of his life. The community to which they moved was full of optimism and self-confidence. Just down the street was the headquarters for Golden State Mutual, and bit further down Johnnie, Sr.’s office. A bit further and you’d find the city’s leading African American newspaper, the Los Angeles Sentinel on Central Avenue and all of the local artistic culture including future jazz greats that came to Central Ave. to learn from the masters.

As Johnnie was wrapping up his time at Mt. Vernon Middle School it occurred to him that he was most interested words and language rather than numbers and he had discovered his passion for debate. While his parents had always envisioned their son to grow up to be a doctor or research scientist young Johnnie Cochran knew that he wanted to be an attorney. Unknown to Johnnie at the time, his father had already gone to work in helping his son achieve his dreams. While most all of the students from Mt. Vernon Middle School were destined to graduate and move on to Dorsey High due to geographic restrictions of the Los Angeles public school system, Johnnie’s father had somehow managed to get him admitted to Los Angeles High school.

Attending L.A. High was a bit of a culture shock for Johnnie. Being the high school for the more affluent neighborhoods in Los Angeles the campus had a fully equipped library, an Olympic sized swimming pool, tennis courts, and clubs and teams for almost any interest you could think of. The competitive atmosphere of the school allowed Johnnie to thrive. He became fluent in Spanish and took classes for French and Italian. His friends were comprised mostly of members of the Honor Society, which he was a member of, and was only open to the top 5 percent of the class. . In 1954 Johnnie was given the inspiration that would shape his future and who he was as a person. He learned that if he embraced the teachings of his parents, if he worked hard and always did his best, that he could have a positive effect on society. It was Spring, and all the way across the country in Washington, D.C. Thurgood Marshall, of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund had fighting the idea of “separate but equal” in the historic case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas.

As a new attorney working for the Los Angeles City Attorney’s Office Johnnie was initially assigned to traffic court. On his very first day he tried 28 traffic tickets and won them all. Not long after he moved up to trying drunk driving and misdemeanor battery cases. In his first two years Johnnie participated in over 125 jury trials and had begun experimenting with the theatrical courtroom demeanor that he had learned from his pastor at Little Union Baptist Church and would later be famous for.

By 1965 Johnnie had become one of the city attorney’s top trial lawyers. Increasingly though he noticed that the cases coming his way were what was called “148s”. This means that the defendants he saw were charged with violating Section 148 of the California Penal Code, or in other words, resisting arrest or interfering with an officer in the course of his duties. LAPD officers privately referred to the penal code section 148 as “the attitude test.” If someone “flunked the attitude test” the officers would administer “curbside justice.”

Johnnie would start each week and see a courtroom filled with men who had “flunked the attitude test.” They invariably displayed visual injuries that would range from cuts and bruises to fractured limbs. Aside from the injuries, 90% of the defendants had another thing in common. They were African American men. The police in Los Angeles had become accustomed to exercising their power virtually unchecked by any authority higher than their own headquarters. From day one it was clear to Johnnie way he and his fellow deputy city attorneys were being asked to prosecute these bogus 148 cases. Through pursuing criminal charges against the men who had “flunked the attitude test”, the city made it virtually impossible for them to file civil suits against the city and be compensated for their injuries.

Through sleepless nights Johnnie began to listen to the voices that had always been with him. C.A.W. Clarke’s sermons in Little Union Baptist Church; “A man cannot serve two masters”, His mother making him promise to be the best that he can be, Thurgood Marshall speaking on the steps of the U.S. Supreme Court, and W.E.B. Dubois describing how Frederick Douglas resolved his own inner struggle. He listened to these voices and in March of 1965 Johnnie left the city attorney’s office and entered into private practice.

Less than a year after the Watts Rebellion the racial tension in Los Angeles once again pushed the city to the brink of civil strife. One night, in May of 1966, Leonard Deadwyler, his pregnant wife Barbara, and a friend were on their way to purchase baby clothes. Barbara began experiencing labor pains and Leonard began to rush her to the L.A. County Medical Center. Before driving off Leonard tied a white cloth to the antenna of his vehicle, a sign of distress in his home state of Georgia. In Los Angeles, unfortunately, the flag held no meaning and when the LAPD patrol cars saw the vehicle speeding toward the hospital the officers were unaware that the occupants were having an emergency.

Leonard, wanting to get his wife to the hospital, continued driving when the officers pulled in behind him. When a second patrol car pulled up beside him the officer inside pointed his gun at Leonard, a practice that is officially reserved for motorists suspected of a felony and ordered them to stop. Leonard pulled to the curb and officer Jerold Bova approached the vehicle with his sidearm drawn. For reasons that he was never able to explain clearly, Bova reached into the driver side window to remove the ignition key which somehow resulted in Leonard being shot in the chest. Bova would later claim that the car had lurched forward and caused him to tighten his grip on the gun in reflex.

Whatever the reason, the shot caused Leonard to fall over into wife’s lap and bleed to death in his own car. Before passing Leonard looked up at the officer who shot him and spoke the last words he would ever say. “But she’s having a baby.”

The killing of Leonard Deadwyler awakened the fury of the African American community in Los Angeles. Angry rumors were spreading, and the anxious city authorities knew that this police shooting could not be handled in the business as usual manner they had grown accustomed to.

Within a day or two Johnnie’s office arranged for the coroner’s office to release Leonard’s body and helped Barbara with funeral arrangements. From the start things were looking suspicious. When the autopsy results came in, they had Leonard’s blood alcohol level at .35, a number that would have left him unconscious and in serious threat of death. Regardless, the police would later use this to claim that Leonard failed to comply with their orders because he was drunk.

The case received an extraordinary amount of attention partly because of the fallout of the Watts Rebellion, but also because the spectacle of police shooting to death a man who was rushing his pregnant wife to the hospital struck a chord in the hearts of a white majority that was previously unwilling to believe that police misconduct ever occurred. Also, the Los Angeles Times and Herald Examiner covered every phase of the case and seven local TV stations devoted an unprecedented amount of time to the subject.

Given the outrage of the community and the media scrutiny it became clear to the civic establishment that they would need to handle the Deadwyler case in an extremely thoughtful manner. District Attorney Evelle J. Younger was the first official to address this fact. He was also the person responsible for deciding whether to prosecute officer Bova for shooting Leonard Deadwyler.

Younger was well aware of the fact that his decision to prosecute Bova, or not, had to be reached in a manner that the majority of the community would accept as fair. He accomplished this by requesting a coroner’s inquest to establish the cause of Leonard Deadwyler’s death. He hoped that a public proceeding would put the facts out into the community and it just so happened that around that time KTLA approached Younger with an idea to televise the inquest. Younger accepted their offer and the Deadwyler Inquest became the first legal proceeding in California history to be carried live on TV.

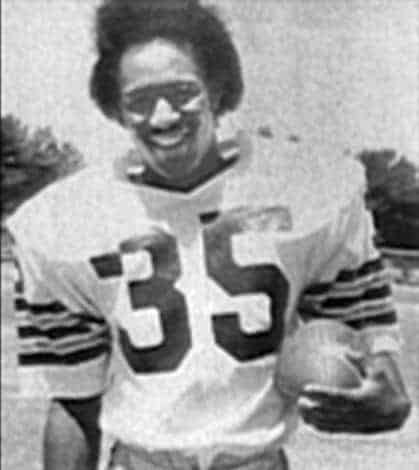

On June 2, 1981 Ron Settles, local football star destined for a professional football career, was traveling to his part-time job as a student teacher and coach at a nearby junior high school. He was running late and decided to take a shortcut through the city of Signal Hill, a city that was notorious for corruption and famously avoided people of color, especially at night. Settles was pulled over by Signal Hill police officer Jerry Lee Brown. The next morning, he was “found” dead in his cell.

The official police story was that Settles was pulled over for driving 47 mph in a 25-mph zone. Officer Brown claimed that as he approached Settles’ vehicle he became “loud and obnoxious” and refused to get out of the vehicle. He further alleged that, after calling for back up, Settles pulled out a nine-inch knife. After Settles surrendered they alleged that they found a “cocaine kit” consisting of a spoon, razor, plastic card, and a small vial containing cocaine residue. They first said the kit was found “around” his car, but later said they found it in the trunk. The officers took him to Signal Hill police station where they charged him with failing to produce ID, possession of cocaine, resisting arrest, and assaulting an officer. The police said that Settles initially declined his legally entitled phone call but phoned his mother an hour later who immediately made arrangements to post bail. Prior to posting bail, the police alleged that at 2:35 P.M. an officer went to Settles’ cell where he found him hanging from the bars with a mattress cover around his neck.

Mr. Cochran sat and listened to Helen and Donell Settles tell the story of their son’s death in silence. The Settles family was very close and Helen and Donell said that there was absolutely no way that Ron took drugs or that he would take his own life. Because there were no non-police witnesses and that police would lie to protect one another Mr. Cochran explained to the parents how seemingly hopeless and expensive any litigation would be. After discussing the matter with the family Johnnie Cochran promised to help them find out what happened to their son and he began preparing for the coroner’s inquest that was scheduled to being in two months.

The coroner’s inquest lasted for 11 days and nearly 30 witnesses testified. One of the witnesses, a white attorney from Long Beach who watched the arrest, flatly contradicted the police department’s account of the incident. Another witness, an inmate in the jail at the time, testified that he had overheard at least two times that police had beaten Ron Settles and was curiously removed from his cell before the police “discovered” Ron’s body. Furthermore, he and another inmate, who had previously occupied the cell where Settles was placed, testified that there was no mattress cover on the bunk. None of the coroner’s tests found any trace of any drug in Ron’s body. Six of the seven officers involved invoked their Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination when asked to testify. Three months to the day after Ron Settles’ body was found the coroner’s jury found that Mr. Settles had died at the hands of another, but because of the police department’s conspiracy of silence there was no one to hold accountable and any claim against the city of Signal Hill seemed as hopeless as learning what had actually happened to Mr. Settles.

Johnnie Cochran determined what their next step should be. He met with Helen and Donnell Settles and asked for permission to exhume Ron’s body to have an independent autopsy performed. With their blessing Mr. Cochran contacted Michael Baden, the country’s finest forensic pathologist, and Sidney Weinberg, both of whom were then working in New York. The independent autopsy found broken bones, dozens of bruises on Ron’s face, neck and upper torso, and what Mr. Cochran had suspected all along – esophageal hemorrhaging. Ron’s windpipe had been crushed against his spine. Additionally, no traces of any drugs were found. Soon after Mr. Cochran phoned Ron’s parents and said, “I’m sorry it took so long, but we now know what happened to your son. They beat him, then they put him in a choke hold, and he died. We may not find a living witness, but because of your courage in letting us go ahead with this, Ron came back from the grave to tell us what happened to him. He could never have done that without you.

Johnnie L. Cochran, Jr. was born on October 2, 1937 in Shreveport, Louisiana. His great-grandparents were slaves, and his grandfather was a sharecropper. His father, Johnnie Cochran, Sr., and mother, Hattie B. Cochran, instilled in Johnnie a work ethic that would take him from the Jim Crow Era South to the upper echelon of the American Legal System. Young Johnnie grew up with two sisters, Pearl and Martha Jean, and the siblings grew up in a time when Louisiana was still dealing with effects of The Great Depression and with Jim Crow laws still deeply entrenched. Despite the times, Johnnies time in Shreveport was a happy time and the memories that always stayed with him were made on Sundays with his family and his church.

In the fall of 1943 Johnnie’s father set out to California and quickly found work as a pipe fitter with Bethlehem Steel in the Alameda Naval Shipyards. Just as the young Johnnie Cochran was turning six he and his family boarded the Southern Pacific and headed to California as part of the second wave of the Great Migration, where 6 million African Americans moved to the Northeast, Midwest and West. Initially they lived with Aunt Lucinda, but soon found their own place near the shipyard. It was the family’s first experience with an integrated neighborhood where working class people of all races and religions lived side by side.

While his parents were always imparting the importance of education and hard work, during their time in the bay area his father also instilled young Johnnie’s love of sports and it was in sports where he would find his first role models outside of family and church. Johnnie remembered back in those days, how his father and his friends would say that Jackie was not even the best player in the Negro League. Naturally, the inquisitive young Johnnie asked his father why, if he was not the best, was he the first? His father’s answer would impact the young man for the rest of his life. He said, “because Jackie was best able to handle it.” Johnnie’s father was preparing him for the hard fact that the bar would always be set a little higher him, regardless of his natural talents.

As World War II drew to a close, so did the family’s time in Alameda. As production in the shipyard was drawing back after the Allied victory, Johnnie’s father was recruited by Golden State Mutual, California’s leading black-owned insurance company. Being the man he was, Johnnie’s father quickly became the company’s top-selling agent, and he was offered a promotion as manager of its San Diego office. The family moved in 1948 and while they did not stay long Johnnie’s time there would see another important Sunday for him. This was the year, while attending services at Bethel Baptist Church, that Johnnie made the decision to live his life for the Lord. The preacher was Reverend Charles Hampton and the verse was John 3:16. At the end of the sermon Johnnie made an agreement with the Lord that he would never regret.

In 1949, a year after accepting his promotion and moving to San Diego, Johnnie Cochran, Sr. was offered another promotion and was asked to move to Los Angeles, where Golden State Mutual was headquartered. The family packed their belongings once again and moved to the city that Johnnie L. Cochran, Jr. would call home for the rest of his life. The community to which they moved was full of optimism and self-confidence. Just down the street was the headquarters for Golden State Mutual, and bit further down Johnnie, Sr.’s office. A bit further and you’d find the city’s leading African American newspaper, the Los Angeles Sentinel on Central Avenue and all of the local artistic culture including future jazz greats that came to Central Ave. to learn from the masters.

As Johnnie was wrapping up his time at Mt. Vernon Middle School it occurred to him that he was most interested words and language rather than numbers and he had discovered his passion for debate. While his parents had always envisioned their son to grow up to be a doctor or research scientist young Johnnie Cochran knew that he wanted to be an attorney. Unknown to Johnnie at the time, his father had already gone to work in helping his son achieve his dreams. While most all of the students from Mt. Vernon Middle School were destined to graduate and move on to Dorsey High due to geographic restrictions of the Los Angeles public school system, Johnnie’s father had somehow managed to get him admitted to Los Angeles High school.

Attending L.A. High was a bit of a culture shock for Johnnie. Being the high school for the more affluent neighborhoods in Los Angeles the campus had a fully equipped library, an Olympic sized swimming pool, tennis courts, and clubs and teams for almost any interest you could think of. The competitive atmosphere of the school allowed Johnnie to thrive. He became fluent in Spanish and took classes for French and Italian. His friends were comprised mostly of members of the Honor Society, which he was a member of, and was only open to the top 5 percent of the class. . In 1954 Johnnie was given the inspiration that would shape his future and who he was as a person. He learned that if he embraced the teachings of his parents, if he worked hard and always did his best, that he could have a positive effect on society. It was Spring, and all the way across the country in Washington, D.C. Thurgood Marshall, of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund had fighting the idea of “separate but equal” in the historic case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas.

The historic decision that the practice of “separate but equal” facilities was not only unequal, but entirely unconstitutional was the spark that would end racial discrimination in the United States. The man who ensured that this happened and inspired 16-year-old Johnnie L. Cochran, Jr. in a way that would change his life forever was Thurgood Marshall. Mr. Cochran immediately began reading anything and everything he could about Thurgood Marshall. To Johnnie, Marshall was living proof that a single dedicated man could use the law to bring about change in society and that is exactly what he set out to do. Despite his mother’s insistence in Johnnie pursuing a career as a doctor, both parents fully supported his decision and after graduating from the University of California, Los Angeles he was enrolled in law school at Loyola Law School.

Johnnie L. Cochran graduated from U.C.L.A. in 1959 and made the decision to attend Loyola Law School. On top of the grueling regimen at Loyola, Johnnie worked, was married in his first year, and had his first child during his third year. He had also found a job in his chosen profession and became the first African American law clerk in the office of the Los Angeles city attorney. The city attorney and his deputies represent the city government and its agencies in all legal matters. When his superiors noticed Johnnie’s fascination with trial work, they assigned him to represent the city in small claims court. On June 1, 1962 Johnnie graduated from Law school and began preparing to take the California bar exam. He took the bar and returned to work at the city attorney’s office to start the month long wait to hear if he had passed. On Monday, December 17th Johnnie was awoken at 2:30 a.m. by a friend who had call with the news that he (the friend) had passed. Johnnie didn’t get back to sleep that night and at 8:30 a.m. he and a colleague called the clerk at the state supreme court to get their results. Not only had Johnnie passed, but two of his closest friends from law school passed as well.

A few weeks later Johnnie knotted his tie and returned to work, not as a clerk but as a freshly minted deputy attorney. On January 10, 1963 Johnnie L. Cochran, Jr. went to work as an attorney for the first time.

As a new attorney working for the Los Angeles City Attorney’s Office Johnnie was initially assigned to traffic court. On his very first day he tried 28 traffic tickets and won them all. Not long after he moved up to trying drunk driving and misdemeanor battery cases. In his first two years Johnnie participated in over 125 jury trials and had begun experimenting with the theatrical courtroom demeanor that he had learned from his pastor at Little Union Baptist Church and would later be famous for.

By 1965 Johnnie had become one of the city attorney’s top trial lawyers. Increasingly though he noticed that the cases coming his way were what was called “148s”. This means that the defendants he saw were charged with violating Section 148 of the California Penal Code, or in other words, resisting arrest or interfering with an officer in the course of his duties. LAPD officers privately referred to the penal code section 148 as “the attitude test.” If someone “flunked the attitude test” the officers would administer “curbside justice.”

Johnnie would start each week and see a courtroom filled with men who had “flunked the attitude test.” They invariably displayed visual injuries that would range from cuts and bruises to fractured limbs. Aside from the injuries, 90% of the defendants had another thing in common. They were African American men. The police in Los Angeles had become accustomed to exercising their power virtually unchecked by any authority higher than their own headquarters. From day one it was clear to Johnnie way he and his fellow deputy city attorneys were being asked to prosecute these bogus 148 cases. Through pursuing criminal charges against the men who had “flunked the attitude test”, the city made it virtually impossible for them to file civil suits against the city and be compensated for their injuries.

Through sleepless nights Johnnie began to listen to the voices that had always been with him. C.A.W. Clarke’s sermons in Little Union Baptist Church; “A man cannot serve two masters”, His mother making him promise to be the best that he can be, Thurgood Marshall speaking on the steps of the U.S. Supreme Court, and W.E.B. Dubois describing how Frederick Douglas resolved his own inner struggle. He listened to these voices and in March of 1965 Johnnie left the city attorney’s office and entered into private practice.

After leaving the city attorney’s office in 1965 Johnnie Cochran opened his first private practice with another former deputy district attorney Gerald D. Lenoir. He was now ready to experience the 148 cases from the other side of the courtroom. Because judges and jurors tended to take the word of practically any police officer over the word of a black defendant there was little Johnnie could do outside of using his contacts in the city attorney’s office to negotiate a deal for his clients. Usually he would have his clients plea “no contest” to a lesser charge of disturbing the peace. While this helped his clients avoid harsher penalties, these cases, and hundreds more like them, were fanning the flames of social anger that were burning just beneath the community’s surface. The same year that Johnnie started his private practice and the same day he moved his family into their new home in Leimert Park this smoldering anger erupted into a full-scale rage in the community of Watts.

The Watts Rebellion, also known as the Watts Riots, lasted for six days. When it was over thirty-five people had been killed and another 1,032 people had been injured. In a 150-block area over 600 buildings had been damaged by looting and arson and, of those, more than 200 had been completely destroyed by the fires. The property loss added up to over $200 million, and 3,938 people and 514 juveniles had been arrested. It just so happened that during this time Johnnie’s law partner was out of town driving his daughters back to school at the University of Wisconsin. With African Americans being arrested in droves the phones of Johnnie’s office were ringing off the hook and the office itself was flooded with clients. There were so many cases pending that the arraignment courts had to work virtually around the clock. Johnnie represented client after client, day after day, and night after night he returned home exhausted.

The Watts Riot renewed Johnnie’s commitment to effect change in the criminal and civil justice systems. He wanted to make the courts, police, and other agencies more responsive to the needs of the community. In the aftermath of the riots Johnnie was optimistic that the disconnect between community and local government could be remedied by working within the system and he had decided the time was right to strike out on his own and start his own practice. Johnnie continued with his criminal defense work and began handling an increasing amount of civil actions. Many of these cases were referred to him by his father or other agents and some of these clients were customers from when he worked for his father selling insurance. The office was so busy that within months Johnnie was joined by a partner, Nelson L. Atkins, another former deputy city attorney. Nelson began working for the City Attorney’s Office after Johnnie had left, but the two knew each other from high school. To Johnnie, Nelson was like a younger brother that he could count on.

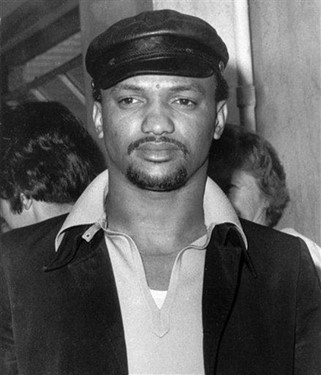

In the mid 1960’s The Black Panther Party rose to national attention with their platform of community determination and meeting racism and oppression with armed struggle. They patrolled their communities, offered free school and clinics, and organized food banks. Soon they found themselves under surveillance by the FBI as well as law enforcement at all levels. The authorities infiltrated and disrupted the organization and even assassinated members. Tensions between the Black Panthers and authorities built over the last half of the decade to the point where in December of 1969 members of LAPD’s Criminal Conspiracy Division, along with FBI agents surrounded the Panther’s Central Avenue headquarters. Over the next five hours the two parties would trade gunfire. The police fired tear gas and the Panther’s threw Molotov’s. The Panther’s eventually surrendered. No one died, but 3 officers and 6 Panthers were injured. Thirteen party members were charged with more than 70 criminal offenses. Johnnie Cochran was appointed to represent a Panther named Willie Stafford. It was here that Johnnie Cochran started his life-long friendship with Elmer “Geronimo” Pratt.

Two years later, in December of 1971, Johnnie Cochran rose to make his closing arguments in defense of Willie Stafford and the other Panther’s on trial with him. Eleven days later the jury reached its verdict. Of the 72 counts alleged against Mr. Cochran’s clients the vast majority of the counts, and all serious charges, came back not guilty. Only 9 Panthers, including Stafford and Pratt, were found guilty of the minor charge of conspiracy to possess contraband weapons. But Geronimo’s problems were just getting started and he asked Mr. Cochran to represent him as he faced murder, robbery and assault with a deadly weapon charges related to another incident.

Police alleged that on December 18, 1968 in Santa Monica Pratt and another man had approached a couple at a public tennis court, ordered them to the ground, robbed them and then shot them, killing 27-year-old Caroline Olsen and injuring 35-year-old Kenneth Olsen. Two years later Kenneth Olsen identified Pratt as “the man who murdered my wife” in the most damning moment in Pratt’s trial. Additionally, a former Blank Panther named Julius Butler also testified that Pratt had confessed to the crime to him and also said he had destroyed the gun used in the crime. In spite of the fact that witnesses had seen Pratt 350 miles away in Oakland during the time of the attack things did not look good for Pratt, but there were also unseen nefarious forces at work against him. Forces that would not come to light until nearly three decades later.

Because Geronimo Pratt was a highly decorated veteran of the Vietnam War, receiving 2 Bronze Stars, a Silver Star and 2 Purple Hearts, he had been specifically targeted by J. Edgar Hoover’s COINTELPRO (Counter Intelligence Program). Papers obtained later under the Freedom of Information Act reveal that Hoover was obsessed with the Black Panthers and had ordered his lieutenants to “neutralize” the party and its leaders. Agents spied on Pratt constantly and the FBI even had wiretap records showing that Pratt made a phone call from Oakland just 3 hours before the Olsen’s were attacked. Additionally, it would later be revealed that Julius Butler was an infiltrator inside the Black Panther Party and an FBI informant despite testifying to the contrary during the trial.

On July 29, 1972, the jury found Pratt guilty on all counts. For the next 27 years Johnnie Cochran never stopped fighting for Pratt. In addition to uncovering the government’s plot against Pratt and the Black Panthers, it was also discovered that the FBI had infiltrated defense sessions during the trial and had wiretapped Mr. Cochran’s calls as well.

Johnnie Cochran continued to build on his reputation throughout the 1980’s and by the time the 1990’s rolled around he was a household name in California and among his legal peers. By the close of the decade Johnnie Cochran, Jr. would be recognized all around the world. He became known, not only as a civil rights and personal injury attorney, but also as the attorney to the stars. By the turn of the millennium Johnnie’s former clients would include Tupac Shakur, Snoop Dogg, Sean Combs, Michael Jackson, Jim Brown, Riddick Bowe and most famously O.J. Simpson. All the while he continued his commitment to represent the little guy; clients like Haitian immigrant Abner Louima, Reginald Denny, Tyisha Miller and Cynthia Wiggins were handled with the same attention to detail as his most famous clients.

The O.J. Simpson trial was viewed all over the world and elevated Johnnie Cochran to become the most famous attorney on the globe. A captivated nation watched the televised trial from June to October of 1995, when at 10:07 A.M. on October 3rd the jury acquitted Simpson on both counts of murder. An estimated 100 million people tuned in to watch the verdict around the world. So many people stopped what they were doing to see the verdict that an estimated $480 million was lost in productivity. While people hailed the trial as The Trial of the Century, closure to another case that had remained most important to Johnnie for more than two decades was just over the horizon.

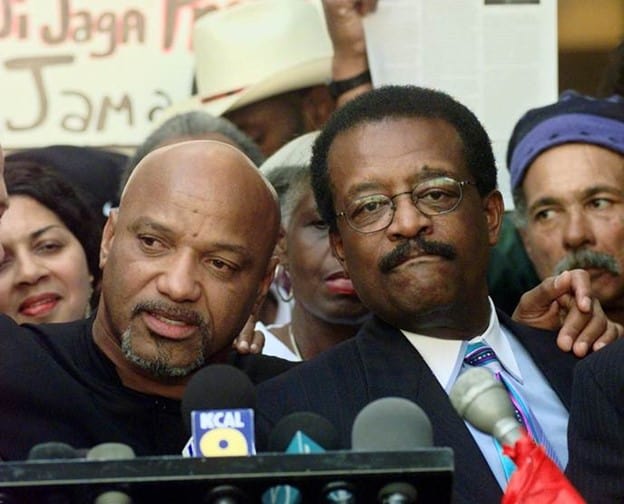

Johnnie continued his work with Black Panther leader Geronimo Pratt who was still serving a sentence for a crime he did not commit. Information had come to light that the prosecution in Pratt’s 1972 trial withheld evidence that included police wiretaps that proved Pratt was in Oakland at the time the murder took place in Santa Monica and that the key witness, Julius Butler, was an informant for the FBI and Los Angeles Police Department. On June 10, 1997 Johnnie Cochran finished his work for Geronimo Pratt when Pratt’s conviction was vacated after 27 years. This became Johnnie’s proudest achievement as an attorney and the two remained close friends until the time of Mr. Cochran’s passing in 2005.

Less than a year after the Watts Rebellion the racial tension in Los Angeles once again pushed the city to the brink of civil strife. One night, in May of 1966, Leonard Deadwyler, his pregnant wife Barbara, and a friend were on their way to purchase baby clothes. Barbara began experiencing labor pains and Leonard began to rush her to the L.A. County Medical Center. Before driving off Leonard tied a white cloth to the antenna of his vehicle, a sign of distress in his home state of Georgia. In Los Angeles, unfortunately, the flag held no meaning and when the LAPD patrol cars saw the vehicle speeding toward the hospital the officers were unaware that the occupants were having an emergency.

Leonard, wanting to get his wife to the hospital, continued driving when the officers pulled in behind him. When a second patrol car pulled up beside him the officer inside pointed his gun at Leonard, a practice that is officially reserved for motorists suspected of a felony and ordered them to stop. Leonard pulled to the curb and officer Jerold Bova approached the vehicle with his sidearm drawn. For reasons that he was never able to explain clearly, Bova reached into the driver side window to remove the ignition key which somehow resulted in Leonard being shot in the chest. Bova would later claim that the car had lurched forward and caused him to tighten his grip on the gun in reflex.

Whatever the reason, the shot caused Leonard to fall over into wife’s lap and bleed to death in his own car. Before passing Leonard looked up at the officer who shot him and spoke the last words he would ever say. “But she’s having a baby.”

The killing of Leonard Deadwyler awakened the fury of the African American community in Los Angeles. Angry rumors were spreading, and the anxious city authorities knew that this police shooting could not be handled in the business as usual manner they had grown accustomed to.

Within a day or two Johnnie’s office arranged for the coroner’s office to release Leonard’s body and helped Barbara with funeral arrangements. From the start things were looking suspicious. When the autopsy results came in, they had Leonard’s blood alcohol level at .35, a number that would have left him unconscious and in serious threat of death. Regardless, the police would later use this to claim that Leonard failed to comply with their orders because he was drunk.

The case received an extraordinary amount of attention partly because of the fallout of the Watts Rebellion, but also because the spectacle of police shooting to death a man who was rushing his pregnant wife to the hospital struck a chord in the hearts of a white majority that was previously unwilling to believe that police misconduct ever occurred. Also, the Los Angeles Times and Herald Examiner covered every phase of the case and seven local TV stations devoted an unprecedented amount of time to the subject.

Given the outrage of the community and the media scrutiny it became clear to the civic establishment that they would need to handle the Deadwyler case in an extremely thoughtful manner. District Attorney Evelle J. Younger was the first official to address this fact. He was also the person responsible for deciding whether to prosecute officer Bova for shooting Leonard Deadwyler.

Younger was well aware of the fact that his decision to prosecute Bova, or not, had to be reached in a manner that the majority of the community would accept as fair. He accomplished this by requesting a coroner’s inquest to establish the cause of Leonard Deadwyler’s death. He hoped that a public proceeding would put the facts out into the community and it just so happened that around that time KTLA approached Younger with an idea to televise the inquest. Younger accepted their offer and the Deadwyler Inquest became the first legal proceeding in California history to be carried live on TV.

In the mid 1960’s The Black Panther Party rose to national attention with their platform of community determination and meeting racism and oppression with armed struggle. They patrolled their communities, offered free school and clinics, and organized food banks. Soon they found themselves under surveillance by the FBI as well as law enforcement at all levels. The authorities infiltrated and disrupted the organization and even assassinated members. Tensions between the Black Panthers and authorities built over the last half of the decade to the point where in December of 1969 members of LAPD’s Criminal Conspiracy Division, along with FBI agents surrounded the Panther’s Central Avenue headquarters. Over the next five hours the two parties would trade gunfire. The police fired tear gas and the Panther’s threw Molotov’s. The Panther’s eventually surrendered. No one died, but 3 officers and 6 Panthers were injured. Thirteen party members were charged with more than 70 criminal offenses. Johnnie Cochran was appointed to represent a Panther named Willie Stafford. It was here that Johnnie Cochran started his life-long friendship with Elmer “Geronimo” Pratt.

Two years later, in December of 1971, Johnnie Cochran rose to make his closing arguments in defense of Willie Stafford and the other Panther’s on trial with him. Eleven days later the jury reached its verdict. Of the 72 counts alleged against Mr. Cochran’s clients the vast majority of the counts, and all serious charges, came back not guilty. Only 9 Panthers, including Stafford and Pratt, were found guilty of the minor charge of conspiracy to possess contraband weapons. But Geronimo’s problems were just getting started and he asked Mr. Cochran to represent him as he faced murder, robbery and assault with a deadly weapon charges related to another incident.

Police alleged that on December 18, 1968 in Santa Monica Pratt and another man had approached a couple at a public tennis court, ordered them to the ground, robbed them and then shot them, killing 27-year-old Caroline Olsen and injuring 35-year-old Kenneth Olsen. Two years later Kenneth Olsen identified Pratt as “the man who murdered my wife” in the most damning moment in Pratt’s trial. Additionally, a former Blank Panther named Julius Butler also testified that Pratt had confessed to the crime to him and also said he had destroyed the gun used in the crime. In spite of the fact that witnesses had seen Pratt 350 miles away in Oakland during the time of the attack things did not look good for Pratt, but there were also unseen nefarious forces at work against him. Forces that would not come to light until nearly three decades later.

Because Geronimo Pratt was a highly decorated veteran of the Vietnam War, receiving 2 Bronze Stars, a Silver Star and 2 Purple Hearts, he had been specifically targeted by J. Edgar Hoover’s COINTELPRO (Counter Intelligence Program). Papers obtained later under the Freedom of Information Act reveal that Hoover was obsessed with the Black Panthers and had ordered his lieutenants to “neutralize” the party and its leaders. Agents spied on Pratt constantly and the FBI even had wiretap records showing that Pratt made a phone call from Oakland just 3 hours before the Olsen’s were attacked. Additionally, it would later be revealed that Julius Butler was an infiltrator inside the Black Panther Party and an FBI informant despite testifying to the contrary during the trial.

On July 29, 1972, the jury found Pratt guilty on all counts. For the next 27 years Johnnie Cochran never stopped fighting for Pratt. In addition to uncovering the government’s plot against Pratt and the Black Panthers, it was also discovered that the FBI had infiltrated defense sessions during the trial and had wiretapped Mr. Cochran’s calls as well.

On June 2, 1981 Ron Settles, local football star destined for a professional football career, was traveling to his part-time job as a student teacher and coach at a nearby junior high school. He was running late and decided to take a shortcut through the city of Signal Hill, a city that was notorious for corruption and famously avoided people of color, especially at night. Settles was pulled over by Signal Hill police officer Jerry Lee Brown. The next morning, he was “found” dead in his cell.

The official police story was that Settles was pulled over for driving 47 mph in a 25-mph zone. Officer Brown claimed that as he approached Settles’ vehicle he became “loud and obnoxious” and refused to get out of the vehicle. He further alleged that, after calling for back up, Settles pulled out a nine-inch knife. After Settles surrendered they alleged that they found a “cocaine kit” consisting of a spoon, razor, plastic card, and a small vial containing cocaine residue. They first said the kit was found “around” his car, but later said they found it in the trunk. The officers took him to Signal Hill police station where they charged him with failing to produce ID, possession of cocaine, resisting arrest, and assaulting an officer. The police said that Settles initially declined his legally entitled phone call but phoned his mother an hour later who immediately made arrangements to post bail. Prior to posting bail, the police alleged that at 2:35 P.M. an officer went to Settles’ cell where he found him hanging from the bars with a mattress cover around his neck.

Mr. Cochran sat and listened to Helen and Donell Settles tell the story of their son’s death in silence. The Settles family was very close and Helen and Donell said that there was absolutely no way that Ron took drugs or that he would take his own life. Because there were no non-police witnesses and that police would lie to protect one another Mr. Cochran explained to the parents how seemingly hopeless and expensive any litigation would be. After discussing the matter with the family Johnnie Cochran promised to help them find out what happened to their son and he began preparing for the coroner’s inquest that was scheduled to being in two months.

The coroner’s inquest lasted for 11 days and nearly 30 witnesses testified. One of the witnesses, a white attorney from Long Beach who watched the arrest, flatly contradicted the police department’s account of the incident. Another witness, an inmate in the jail at the time, testified that he had overheard at least two times that police had beaten Ron Settles and was curiously removed from his cell before the police “discovered” Ron’s body. Furthermore, he and another inmate, who had previously occupied the cell where Settles was placed, testified that there was no mattress cover on the bunk. None of the coroner’s tests found any trace of any drug in Ron’s body. Six of the seven officers involved invoked their Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination when asked to testify. Three months to the day after Ron Settles’ body was found the coroner’s jury found that Mr. Settles had died at the hands of another, but because of the police department’s conspiracy of silence there was no one to hold accountable and any claim against the city of Signal Hill seemed as hopeless as learning what had actually happened to Mr. Settles.

Johnnie Cochran determined what their next step should be. He met with Helen and Donnell Settles and asked for permission to exhume Ron’s body to have an independent autopsy performed. With their blessing Mr. Cochran contacted Michael Baden, the country’s finest forensic pathologist, and Sidney Weinberg, both of whom were then working in New York. The independent autopsy found broken bones, dozens of bruises on Ron’s face, neck and upper torso, and what Mr. Cochran had suspected all along – esophageal hemorrhaging. Ron’s windpipe had been crushed against his spine. Additionally, no traces of any drugs were found. Soon after Mr. Cochran phoned Ron’s parents and said, “I’m sorry it took so long, but we now know what happened to your son. They beat him, then they put him in a choke hold, and he died. We may not find a living witness, but because of your courage in letting us go ahead with this, Ron came back from the grave to tell us what happened to him. He could never have done that without you.

Johnnie Cochran continued to build on his reputation throughout the 1980’s and by the time the 1990’s rolled around he was a household name in California and among his legal peers. By the close of the decade Johnnie Cochran, Jr. would be recognized all around the world. He became known, not only as a civil rights and personal injury attorney, but also as the attorney to the stars. By the turn of the millennium Johnnie’s former clients would include Tupac Shakur, Snoop Dogg, Sean Combs, Michael Jackson, Jim Brown, Riddick Bowe and most famously O.J. Simpson. All the while he continued his commitment to represent the little guy; clients like Haitian immigrant Abner Louima, Reginald Denny, Tyisha Miller and Cynthia Wiggins were handled with the same attention to detail as his most famous clients.

The O.J. Simpson trial was viewed all over the world and elevated Johnnie Cochran to become the most famous attorney on the globe. A captivated nation watched the televised trial from June to October of 1995, when at 10:07 A.M. on October 3rd the jury acquitted Simpson on both counts of murder. An estimated 100 million people tuned in to watch the verdict around the world. So many people stopped what they were doing to see the verdict that an estimated $480 million was lost in productivity. While people hailed the trial as The Trial of the Century, closure to another case that had remained most important to Johnnie for more than two decades was just over the horizon.

Johnnie continued his work with Black Panther leader Geronimo Pratt who was still serving a sentence for a crime he did not commit. Information had come to light that the prosecution in Pratt’s 1972 trial withheld evidence that included police wiretaps that proved Pratt was in Oakland at the time the murder took place in Santa Monica and that the key witness, Julius Butler, was an informant for the FBI and Los Angeles Police Department. On June 10, 1997 Johnnie Cochran finished his work for Geronimo Pratt when Pratt’s conviction was vacated after 27 years. This became Johnnie’s proudest achievement as an attorney and the two remained close friends until the time of Mr. Cochran’s passing in 2005.

Johnnie Cochran had long dreamed of creating a national law firm made up of men and women from all races, religions, creeds, and backgrounds to show how well we could all work together to make the world a better place. In 1998, in a classic case of being in the right place at the right time, Johnnie would see his national firm materialize. Johnnie had been speaking to his friend and prominent attorney Jock Smith about his aspirations of building a national firm. While attending an attorney convention in New Orleans Jock was visiting with Keith Givens, a friend and colleague. Jock began describing his conversations with Mr. Cochran to Givens, who he knew could help implement Johnnie’s vision and asked if he would agree to meet with Mr. Cochran. Givens agreed and started pitching ideas back and forth with Mr. Cochran. The two soon became inseparable with hardly a day passing that they were not on the phone discussing their plans. Givens brought in his law partner Samuel Cherry and soon after Johnnie Cochran, Jock Smith, Keith Givens and Samuel Cherry became the founding partners of Cochran, Cherry, Givens & Smith, the law firm that would soon become The Cochran Firm.

The four founders spent the following years partnering with prominent attorneys in major cities across the nation. Jock Smith was named as the first President of The Cochran Firm after Mr. Cochran passed in 2005 and continued to build the foundation on which The Firm sits today. After Jock passed in 2012 Hezekiah Sistrunk, Jr. was named president in 2013 and established The Firm’s Board of Directors in 2018. The original members the board were Hezekiah Sistrunk, Jr., Keith Givens, Samuel Cherry, Derek Sells, Shean Williams, Angela Mason and Jeffrey Mitchell. In 2019 the board welcomed Brian Dunn and Karen Evans. The leadership and attorneys of The Cochran Firm continue the legacy of Johnnie L. Cochran, Jr. by providing valuable legal representation based on the principles and philosophy developed by Johnnie himself.

Despite his notoriety and list of famous clients and friends, Johnnie Cochran never lost sight of his mission to bring access to justice to people from all walks of life. While expanding his firm to a national platform Mr. Cochran knew he would have to surround himself with likeminded attorneys who shared his commitment to justice, attorneys he could trust to continue his legacy.

Our Legal Legends section is dedicated to the memory of Cochran Firm attorneys from across the U.S. who helped Mr. Cochran build and realize his dream of a nation – wide law firm dedicated to standing up for the little guy.

Haga clic para leer en español.

December 9, 1941 – December 11, 2007

Randall “Randy” Mainor was born in Overton, Nevada in 1941. After his graduation from high school in 1960 he attended the College of Southern Utah and Brigham Young University earning his bachelor’s degree in economics with a minor in Spanish. In 1969 Randy earned his law degree from American University. Before going into private practice, Randy was employed with the FBI as a special agent and a criminal prosecutor with the District Attorney’s Office.

LEARN MORE

December 9, 1941 – December 11, 2007

Born in New York City in 1940, Phillip Damashek was educated at the University of Miami and admitted to the New York State bar in 1969. He helped to build his prestigious New York law firm Schneider, Kleinick, Weitz, Damachek & Shoot for forty years before merging with The Cochran Firm. During that time, he was a visionary in the legal field by being one of the very first attorneys to advertise his services in 1978 after the supreme court determined that attorney advertising was legal.

LEARN MORE

October 20, 1931 – January 5, 2017

Ivan Schneider grew up in Brooklyn and graduated from Brooklyn Law School in 1953. He is credited with obtaining more than 200 multimillion-dollar verdicts and settlements for his clients. In his half century long career Ivan was regularly named as one of the top trial lawyers in New York City. He was a founding partner in Schneider, Kleinick and Weitz which merged with Damshek, Godosky and Gentile in 1994 to become Schneider, Kleinick, Weitz, Damashek and Shoot.

LEARN MORE